Introduction

Well! It’s been a long time since I’ve shared an Accrescent update here (most development discussion takes place in our Matrix rooms), but today I have a big one: we’ve made significant progress in developing delta updates!

“That sounds great and fancy!” I hear you say, “but what in the world are delta updates, and why would I care?”

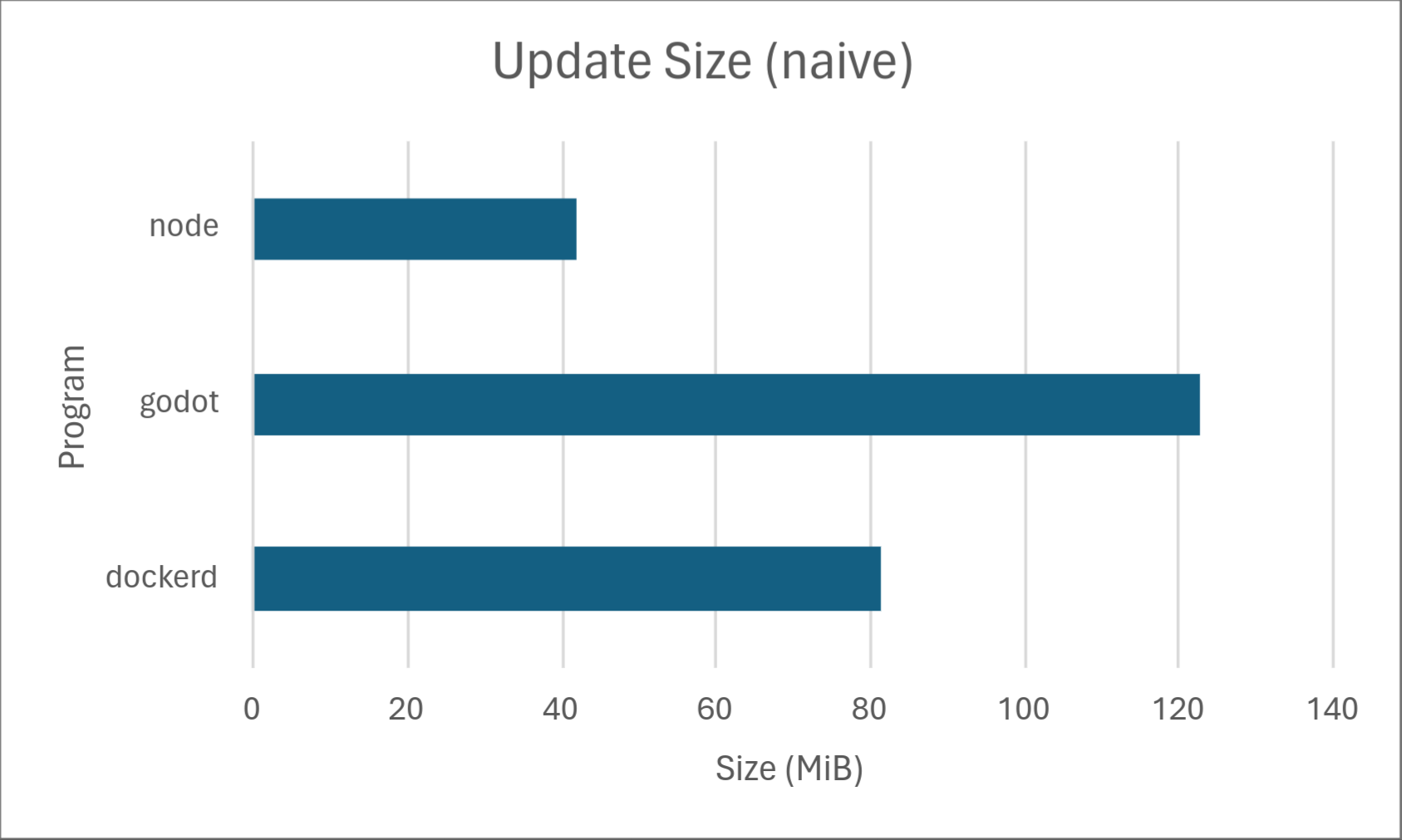

Well, to give a quick summary, delta updates bring your software update sizes from looking like this:

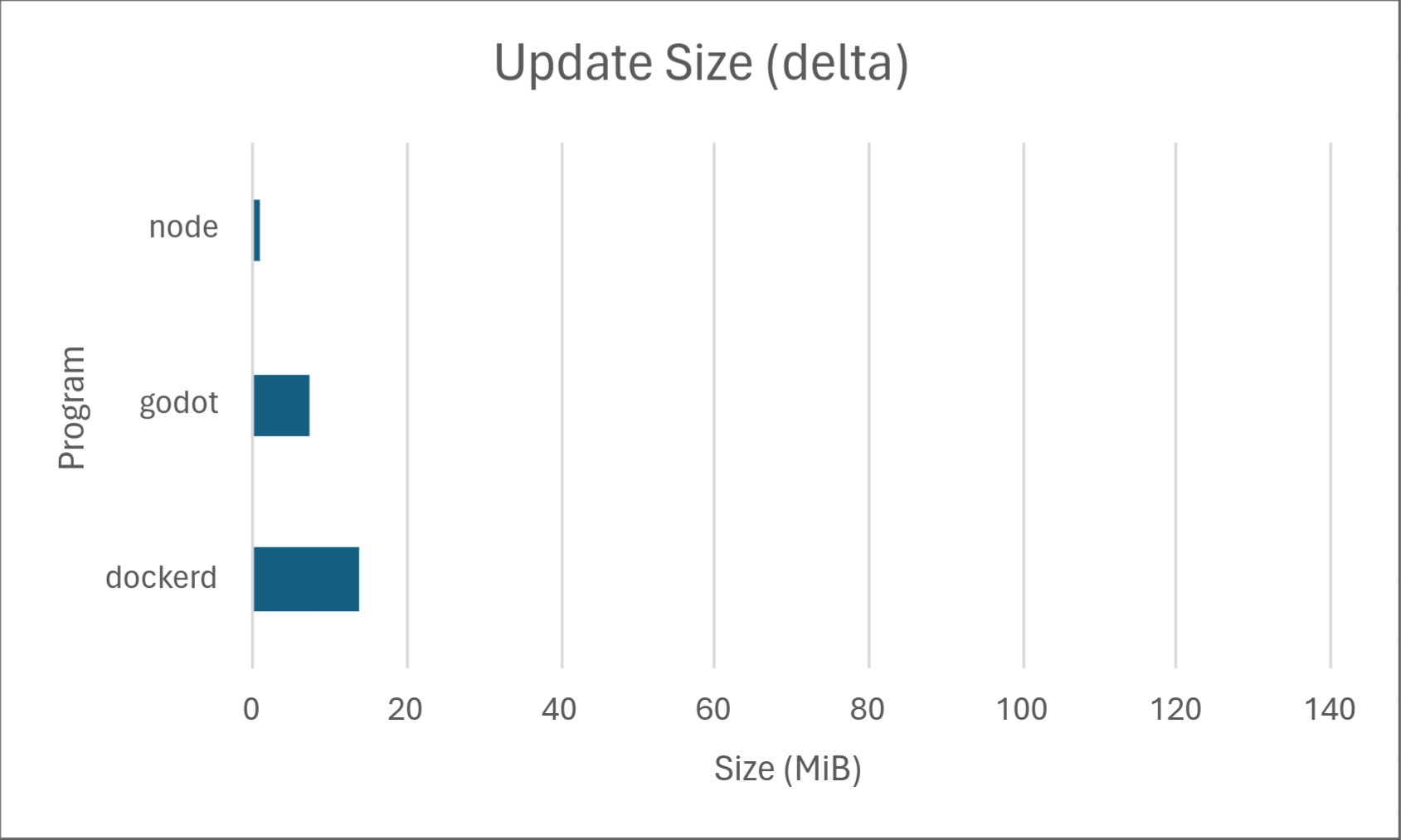

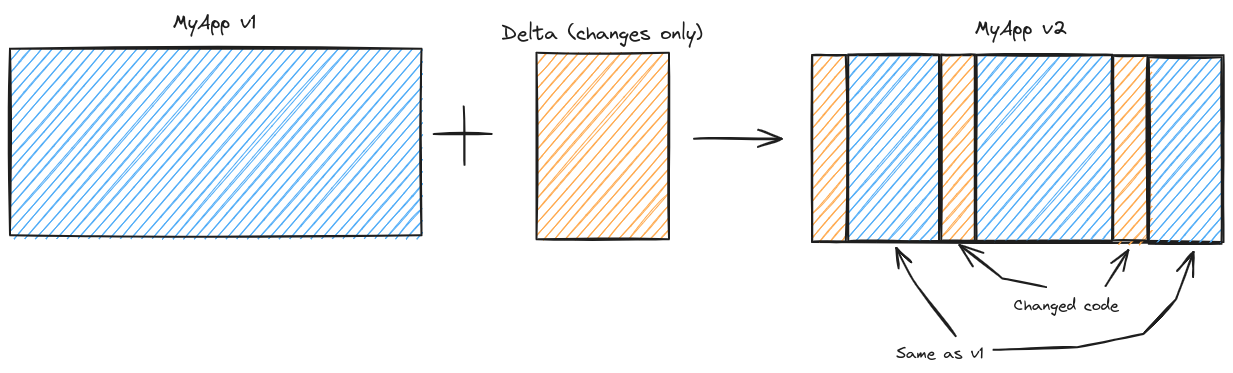

to this:

If you’re curious as to how, keep reading. 1

Background

In a basic software update system, the update process looks something like this:

- Download the newest version of the software to disk.

- Replace the old software files with the new ones.

For the sake of convenience, we’ll refer to this process as the “naive approach.”

There isn’t anything wrong with the naive approach per se; it’s simple, it works, and it’s relatively easy to implement. Many software update systems still work this way. However, when working with wide-scale deployments, the naive approach suffers from a considerable issue: a full copy of the latest software must be distributed to each client. 2

This in turn causes higher bandwidth costs for both clients and the server operator, less frequent updates (which may contain security fixes!), slower rollout, and more update interruptions which may require starting the update over from the beginning. The client-facing issues are especially troublesome in countries where Wi-Fi isn’t commonplace and cellular data is slow and expensive. Clearly, a solution to reduce these update sizes would be beneficial for both clients and the update server operator. But how can we do this?

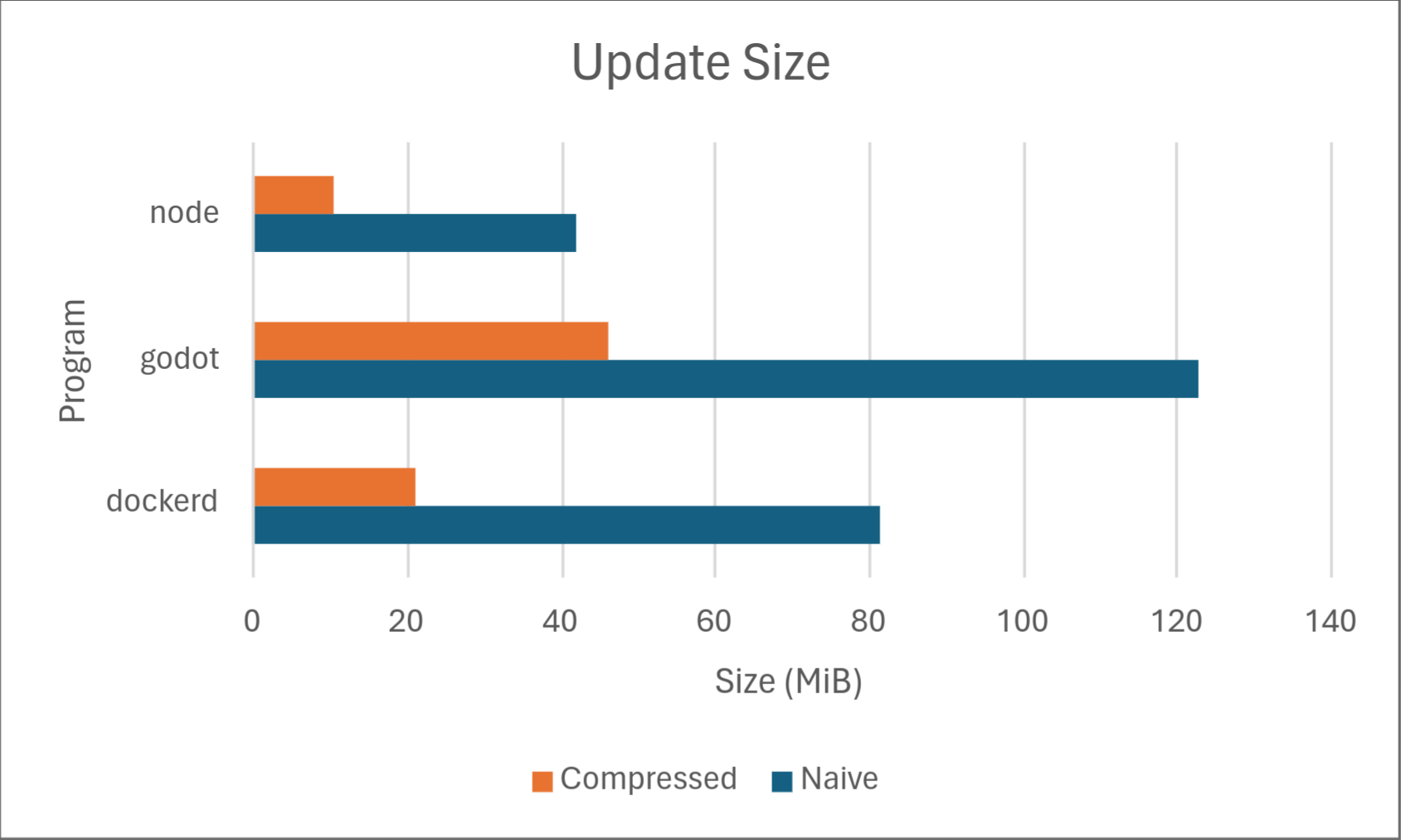

Attempt 1: Data compression

Perhaps the most obvious first step to reduce update size is to apply generic data compression. Using zstd at level 19, we get the following results:

Not bad! But these results are still far from the delta update sizes shown in the introduction. So how can we possibly reduce them further?

Data compression in theory

While deep data compression theory is outside the scope of this article, a brief description of how data compression works will help understand the approach to solving this problem. In general, data compression algorithms exploit patterns in data to represent said data in fewer bytes. For example, say we want to compress the sequence “AAAA”. We easily see that we’re only using one character, A, and that it repeats four times. We could design a compression scheme which exploits this pattern by encoding it as a character followed by how many repeats of that character exist. 3 In this example, we could compress our input sequence to “A4,” a 50% size reduction.

Another important concept to understand is that the more you know about the type and format of the data you’re compressing, the more specific patterns you can detect and potentially exploit to reduce compressed file size. Expanding the above example, let’s say we know that our data contains only the characters “A” and “B.” Thus, we can represent each character as 1 bit (0 representing A, and 1 representing B). If our length value is encoded as 8 bits, we can then represent “A4” in 9 bits (as opposed to the 16 we would use if encoding “A” an as ASCII value).

With that out of the way, let’s move on to delta updates!

Attempt 2: Delta updates

We’ve discussed how data compression exploits patterns to represent data in fewer bytes. So what patterns exist in software updates that we can exploit to reduce the size of our software updates? As it turns out, there are two very important ones:

- The new software is usually very similar to the old software with some sparse changes.

- The files being updated are usually executable software.

We’ll leave the second point up for discussion in part 2 of this series where we’ll explain the algorithm that Accrescent’s delta update system uses in more detail. The first point is more fundamental to delta update algorithms in general, and it prompts the question: if the new software is mostly the same as the old software, what if we encoded only the differences between the two and just copied data from the old software when it hasn’t changed? That is, instead of viewing a software update like this:

what if we viewed it like this:

and only sent the changes to the client? 4

Here we have arrived at the concept of delta updates.

Our solution

Delta updates themselves are not a novel idea. Windows, Google Play, Chrome, Android, and more use some form of delta updates to reduce software update sizes. Some of these are partially or completely open-source, making it theoretically possible to adapt one of them for Accrescent’s usage. However, existing implementations suffer from some or all of the following issues, some of them directly counter to Accrescent’s goals:

- They are written in memory-unsafe languages like C and C++, making them prone to security vulnerabilities and thus undesirable to use in a security-sensitive context.

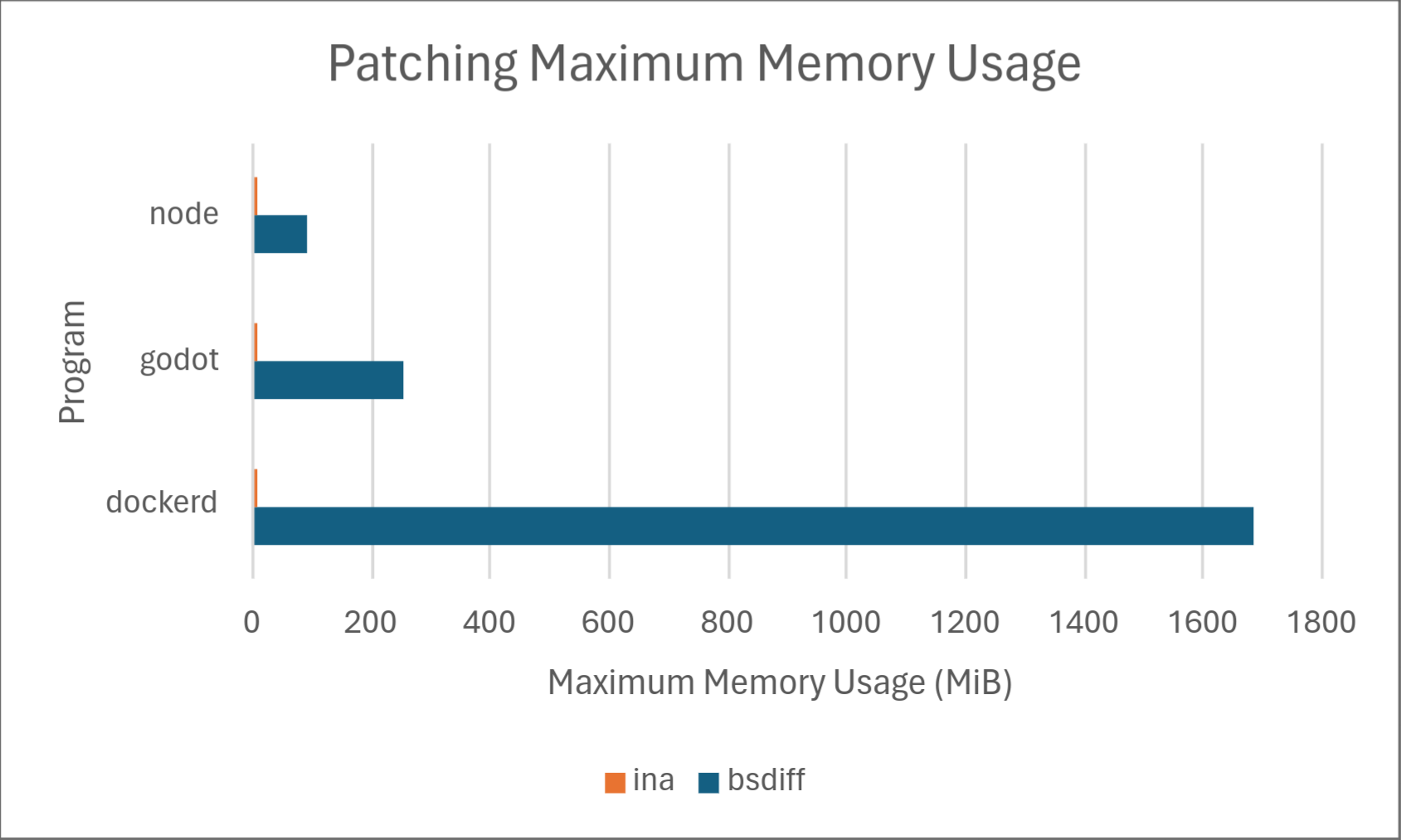

- They use an excess of main memory when diffing (creating a delta update) and/or patching (applying a delta update), making them unsuitable for devices with low memory such as mobile phones and some VPSs.

- They have little to no testing, raising questions about their correctness and robustness against bug classes outside of memory corruption (which can also be a security concern).

- They have no Android library wrapper.

Because of this, we decided to create a custom solution to the delta update problem with the following goals:

- Memory-safe implementation language

- Low memory requirements

- Batteries-included Android library

- Sandboxed Android patching

- Thorough testing

- Comparable diff and patch performance to existing implementations

We’re happy to say that this effort has been successful with all of the above goals met. 5 We call the resulting library “Ina.”

Performance results

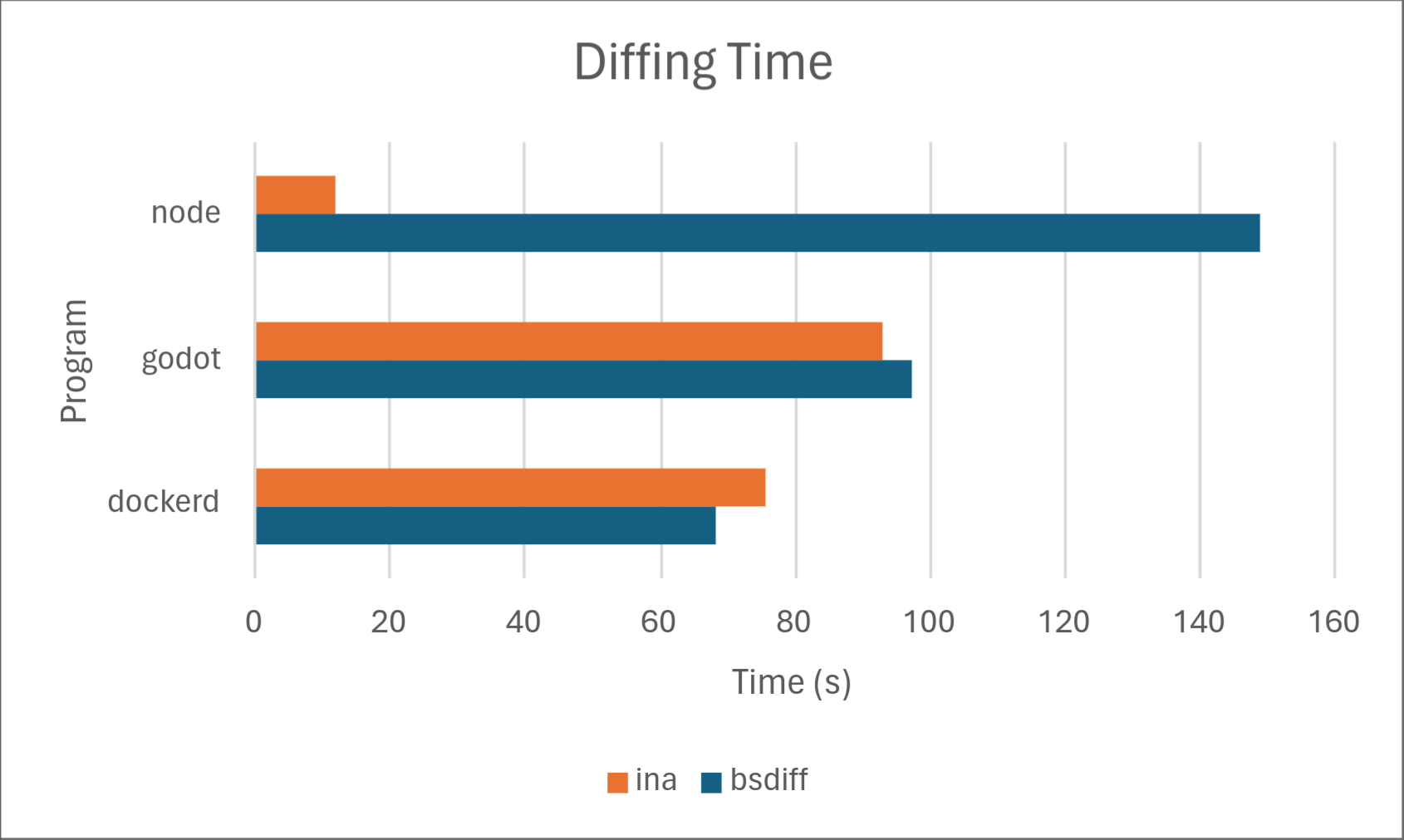

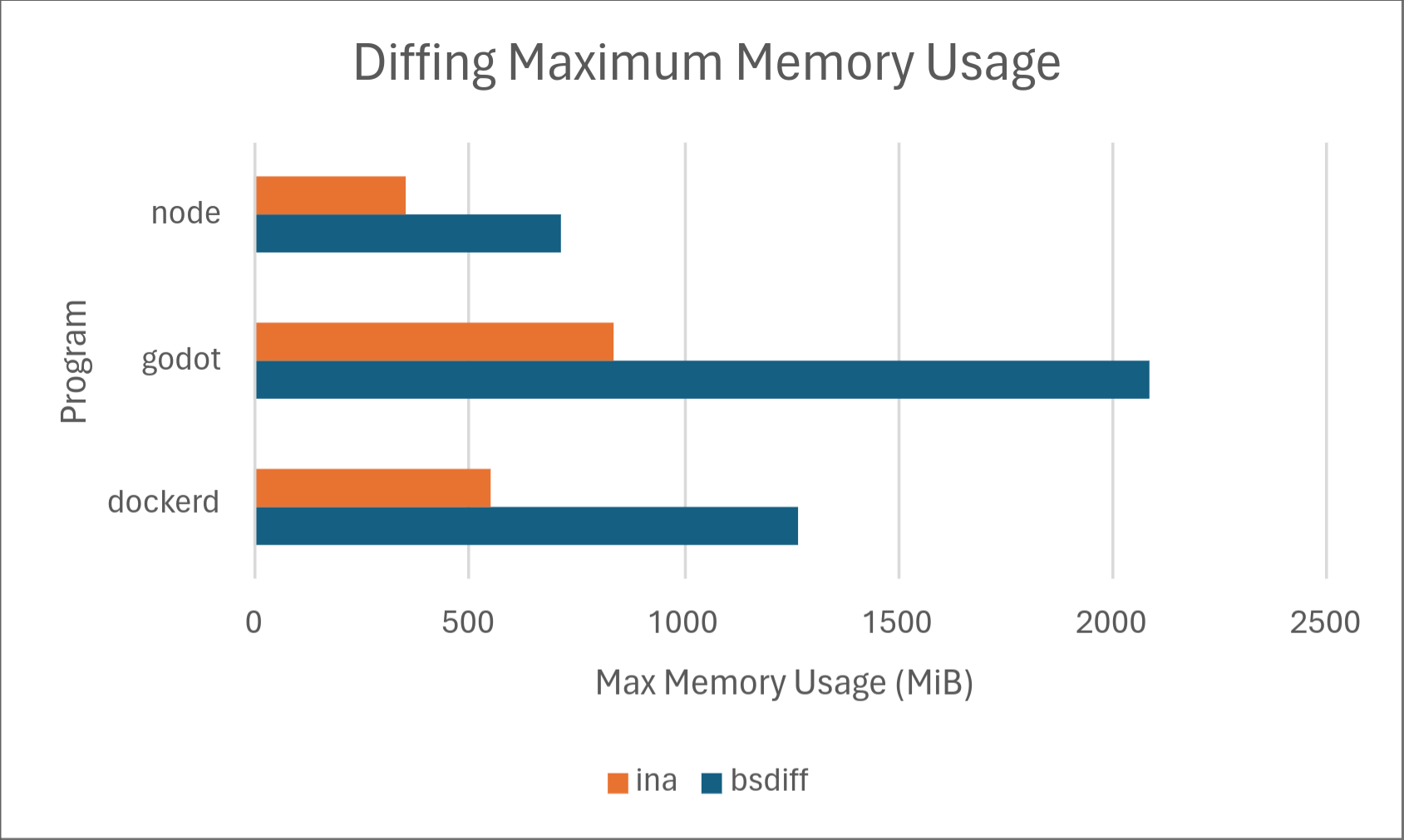

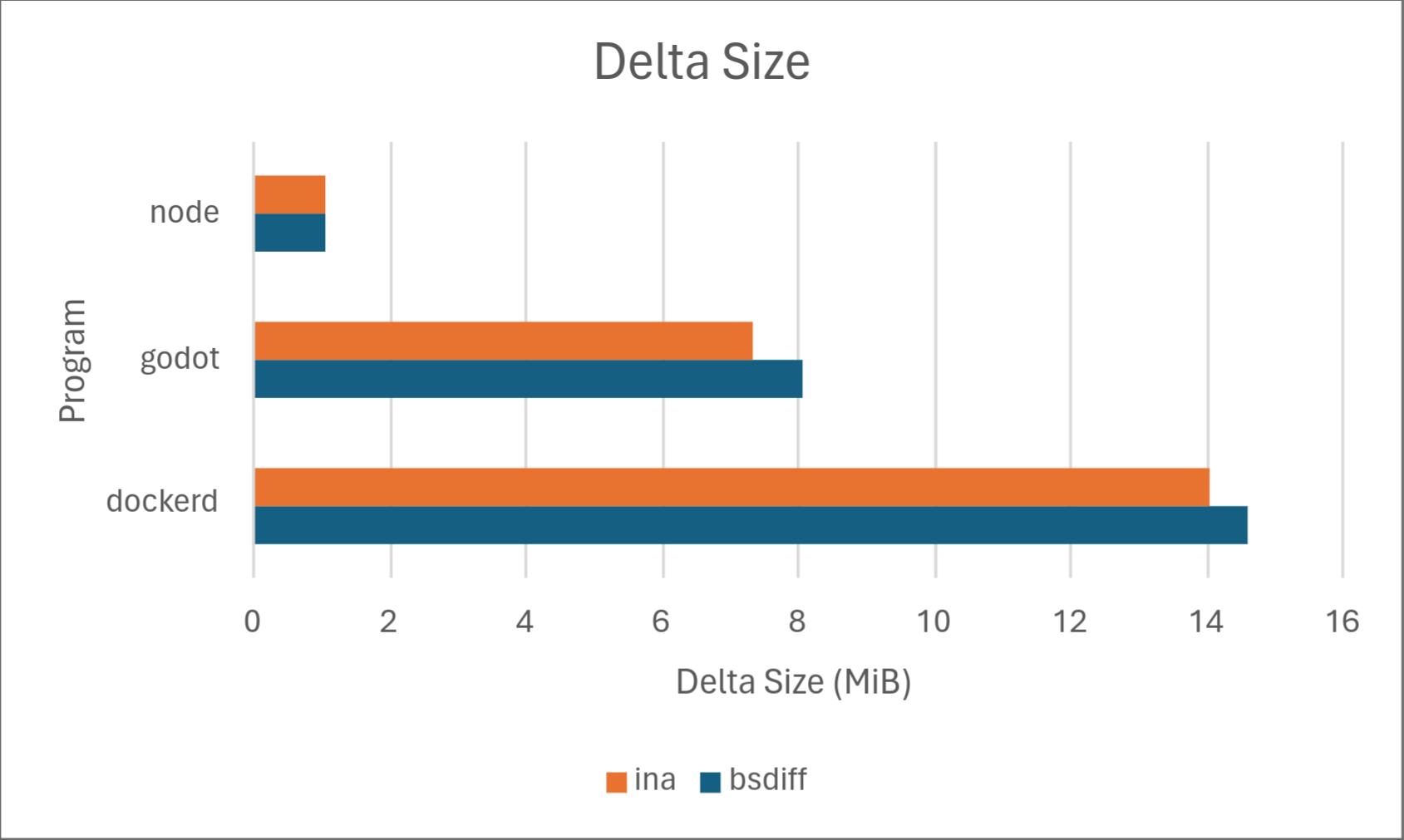

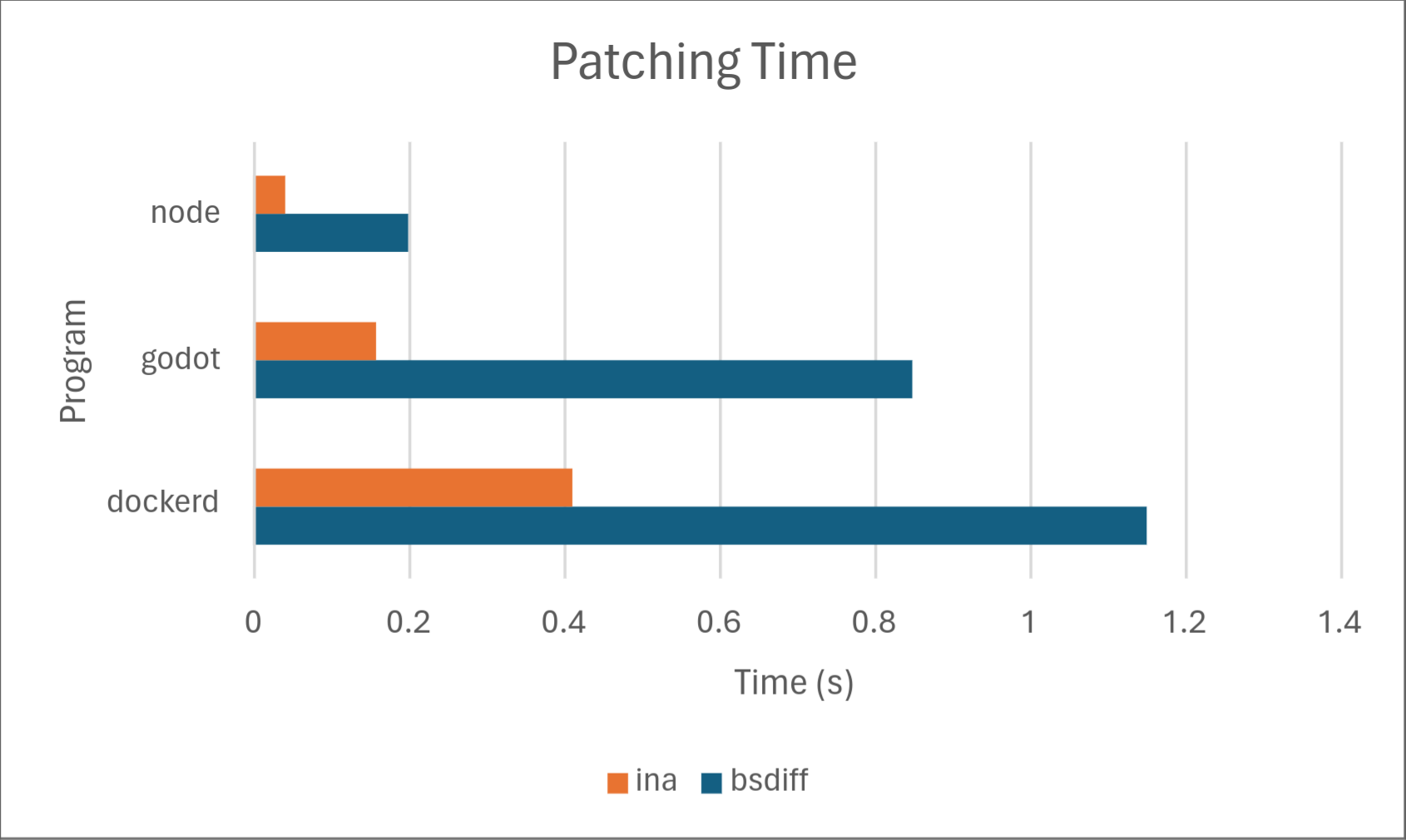

Of course, numbers speak louder than words, so we’ve included some results on how Ina stacks up against the competition, specifically against one of the most common open-source implementations of delta updates: bsdiff. Below are the results.

All numbers were taken as an average of 3 runs on an Arch Linux system with an Intel Core Ultra 7

155H processor and LPDDR5 memory running at 6400 Mhz. The original version of bsdiff 4.3 was

compiled with the default Arch package manager compiler flags plus -O3. Ina was compiled in

release mode without any additional compiler flags. Measurements were taken using GNU time. 1

Analysis

Across the board, Ina consistently uses significantly less memory than bsdiff when both diffing and patching. Diffing time is comparable, with bsdiff taking a slight lead for dockerd, but Ina taking a drastic lead for node. We don’t know the exact cause of this, but may investigate in a later part of this series. Delta size was comparable between the two programs with Ina taking a slight lead. Ina took a drastic lead in patching time. However, it should be noted that patching time may not matter much in practice depending on the hardware because it’s so low to begin with.

Conclusion

We’ve successfully developed a performant, safe, and robust solution for delta updates to incorporate into Accrescent. While there are still ways to improve diffing performance and strengthen the library sandbox, 5 we’ve already made significant security and performance improvements over existing delta update solutions and are confident we can implement the additional improvements we have planned.

In part 2 of this series, we’ll explore exactly how Ina achieves its performance characteristics and perhaps investigate alternative algorithms and performance tricks Ina could take advantage of to further improve its performance.

That’s all for this one! If you want to keep up on more Accrescent developments, join our Matrix rooms, follow the Accrescent socials, or keep an eye on this blog where I’ll be posting the next part of this series on Ina and delta updates.

All numbers in this post are based on the following Arch Linux x86_64 binaries: dockerd 24.0.7 and 25.0.2, node 20.11.0 and 20.11.1, and godot 4.1.2 and 4.1.3. ↩︎ ↩︎

All active clients with a network connection, of course. Not every client will receive every update, especially if the software in question updates frequently, as a newer update may be released before a client attempts to update to the previous release. ↩︎

This is called run-length encoding (RLE). While not often used on its own, RLE is used in practice as a part of many popular compression schemes. ↩︎

This is an oversimplification. Instructions specifying where to place the changes in the new binary and which bytes to copy verbatim from the old binary are also necessary, but I decided to omit this from the diagram as the details of the algorithm will be explained in part 2. ↩︎

The original version of this article stated we didn’t have Android sandboxing implemented. Sandboxing was implemented only a few days later, so we updated the text to reflect this. ↩︎ ↩︎